On November 24, 1971, Northwest Orient Flight 305 took off from Portland International Airport for Seattle-Tacoma International Airport on what should have been a routine flight. Even that early in the Jet Age, it was just a short hop that only cost $20 one way. Instead, that flight became the stuff of legend. The legend turns 50 years old today.

That year, like this year, it was the day before Thanksgiving, and D.B. Cooper was taking the last plane anyone would see him on – as far as they know at least. In honor of that anniversary, Oregon historian Doug Kenck-Crispin has requested the entire file on the so-called “D.B. Cooper” case from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and he has read through all 22,277 pages of that at times heavily redacted file, compiled from 1971 until it gradually ground to a halt, more or less, in 1992, and was eventually declared closed, more or less, in 2016.

Kenck-Crispin is an historian, they do that sort of thing. You can read it, too. He wrote a very entertaining article about it that appeared recently in the Portland Mercury, and on Nov. 24, he’s going to be live-tweeting the events of the hijacking, on the 50th anniversary to the minute that they happened.

November 24, 1971

He bought his ticket under the name “Dan Cooper,” paying cash and showing no ID. In 1971, you could do that.

The flight was quite routine at first. Passengers drank soft drinks or liquor as they preferred – Cooper had a “7&7” – they smoked if they wanted to as that was still perfectly legal and socially acceptable in 1971 – Cooper smoked Raleighs, the FBI noted later. Then that soon-to-be-famous, forever-to-be-anonymous passenger handed a flight attendant a folded note. Thinking it was one more pickup attempt, she tucked it into her pocket, but the handsome man called after her, “You really should read that.” So she did.

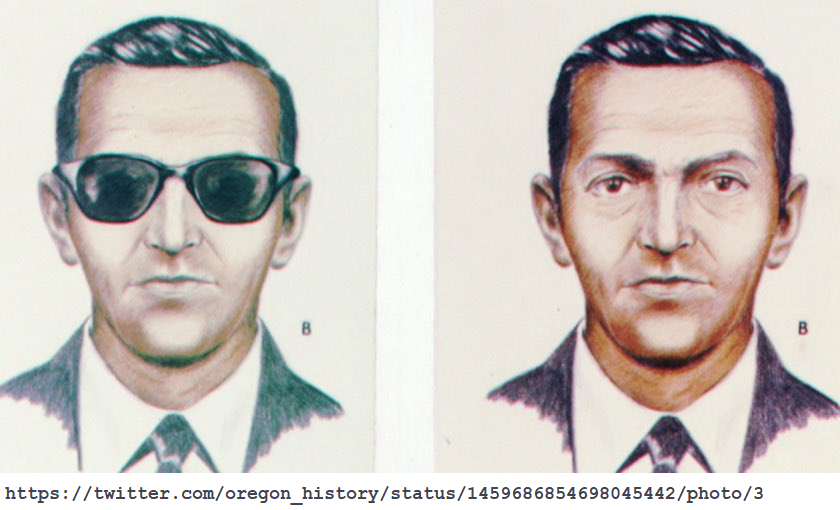

The typed note said the very polite man in the black suit and sunglasses was carrying a bomb.

She went back and bent down next to him. He opened his briefcase to give her a glimpse of a battery, wires, and red tubes bundled together – enough of a view that she felt she couldn’t take any chances. She informed the cabin crew of what she had seen, and what he had said: his exact words were, “No funny stuff, or I’ll do the job.”

When the plane landed in Seattle, the passengers got off. Only the flight crew remained. Two parachutes and a backpack full of twenty-dollar bills were brought aboard in response to the man’s demands. The plane was refueled and took off again towards Reno, and people on the ground and on the plane wondered what would happen next.

Several planes had been hijacked and flown to Cuba by people who for some reason thought they’d be welcomed by Fidel Castro – they hadn’t been and each was arrested and the planes and passengers returned unharmed. But Cooper’s plane wasn’t carrying enough fuel for that flight.

Where did this man have in mind to land?

Did he actually plan to use one of the parachutes he’d asked for, or was that just a ruse to distract the authorities from his true intentions?

As the plane flew over the Columbia River near Portland, Cooper offered his flight attendant one of the bundles of money, but she told him it was against company policy to accept tips. He then strapped on a parachute, tied the backpack of money to his body, lowered the tail ladder, and jumped. He was 10,000 feet up and going 200 miles per hour, it was 10 degrees below freezing and he wore an ordinary black business suit and slip-on loafers.

The Legend

Some people think his story ended right there. That between the cold air and the wind chill, he lost consciousness long before he intended to open his parachute and fell to his death or was dead when he hit the ground – or the river. Others – including skydivers who have offered to duplicate the jump, complete with the slip-on shoes – think it was completely survivable. There’s no way of saying for sure.

What can be said with certainty is that he successfully disappeared. No trace of him has ever been found, except for tantalizing clues that only raise more questions.

In 1980, a boy on a camping trip along the Columbia River was clearing leaves away from a patch of ground to make a safe spot for a campfire, and discovered that some of the “leaves” were decayed twenty-dollar bills. Turned over to the FBI, they were confirmed to be $5,800 of the money Cooper had demanded. Had they fallen from Cooper’s backpack in the air? Had they been dropped by him as he tried to walk out of the wilderness after he landed? Had they been deliberately planted there to throw investigators off the trail? Professional investigators and treasure hunters have raked the area for more of the money and found none.

Later, shreds of his parachute were found and proved equally uninformative. They don’t even tell whether he opened it.

The Hunt

The FBI had a suspicion that a man in The Dalles whose name was “something similar to” D.B. Cooper might be their man. That fact wasn’t supposed to reach the press, but somehow it was picked up by the Oregon Journal, at the time the second-largest newspaper in Oregon. Thus “Dan Cooper” became “D.B. Cooper” in every news report.

But surely a hijacker, even in 1971, wouldn’t really use his own name, would he?

A clue to his background might be found in the fact that since 1954, a comic book has been published throughout the French-speaking world about a Canadian military pilot named Dan Cooper. Some have said that the comic book suggests that the mystery man was an aviation professional, perhaps a paratrooper.

One extreme speculation gains point for tying the hijacking to an equally interesting and much more respectable part of Oregon’s aviation history by suggesting that the swarthy Cooper was the lightest-skinned veteran of the 555th Parachute Infantry – an African American paratrooper unit who were denied the chance to serve overseas, but distinguished themselves fighting forest fires, including those set by Japanese fire balloons. Others have said it indicated the opposite: that he had only an outsider’s interest and at best an amateur’s knowledge of flying and skydiving.

Odd Tidbits

As part of the 50th anniversary, Kenck-Crispin came up with a few other odd facts about this legendary local story.

Cooper might have been spotted at a bar called the Sandy Hut five days after his great skydive. A Portland Police officer was having a drink there in the morning of Nov. 29 and thought an enigmatic stranger breaking hundred-dollar-bills was the man in question. That man was apparently a lawyer from Washington who, while drunk and unable to pinpoint his exact location on the Wednesday in question, was not the guy they were after.

Race played a much larger part in the investigation than many knew. While it has been historically passed down that Cooper was Caucasian, he had an olive or “Latin complexion.” This landed the FBI at the doorstep of the Los Angeles parachute club “Latin Sky-Divers.” They went so far as to have their people look into any “concentration of Mexican-American extremists, including Chicanos [and] Brown Berets,” and even led them to not look at men considered too white.

At one point, a troop of Boy Scouts offered to help look for Cooper. But since they weren’t sure if the bomb had actually been a bomb, and since Boy Scouts tend to be minors, the offer was rejected.

By 1976, it was generally agreed that, even if Cooper were found, it would be very difficult to make the case against him. Yet, the search went on.

A man in Vancouver, Wash. was found of interest to the authorities for carrying clippings of the Cooper case. He admitted that he was only guilty of liking to carry clippings, and he was released.

Another man claimed to be Cooper, although he was considered a “hippie” – something Corvallisites certainly know a thing or two about – and hung with the Black Panthers and American Indian Movement. He also claimed to have given the money to radical movements. The FBI decided that it was unlikely that he was their man.

And Now

What actually happened to “D. B. Cooper,” or even what his real name was, may never be known, but the name the Journal accidentally gave him will probably live for generations to come in song and story, on stage and on screen.

As for the man himself, he didn’t look to be terribly young even in 1971 – he was most likely in his thirties or forties, and he was a drinker and a smoker. It’s understandable why the FBI closed its file in 2016. Even if he did survive his desperate leap into the dark, it seems very likely that by 2021 he will have quietly, privately, passed from legend into myth.

By John M. Burt

Do you have a story for The Advocate? Email editor@corvallisadvocate.com