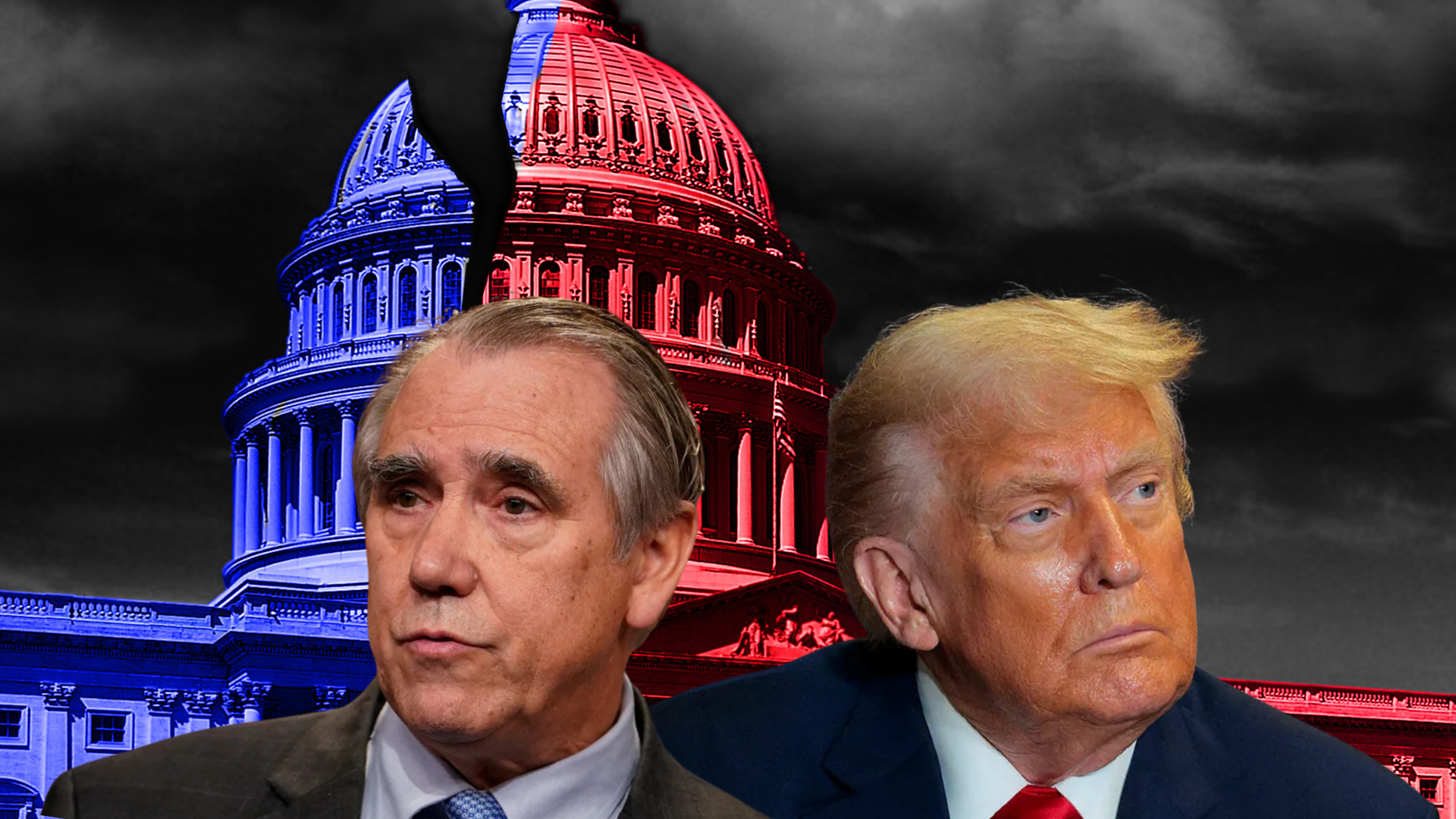

Bet you couldn’t come up with a controversial topic which finds President Donald Trump and Oregon’s Democratic U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley on the same side. Well, more or less.

Bet you couldn’t come up with a controversial topic which finds President Donald Trump and Oregon’s Democratic U.S. Sen. Jeff Merkley on the same side. Well, more or less.

And not only one, but one with implications for the Oregon Legislature.

But here we are: Concern about mass big-money purchases of residential property.

President Trump on Jan. 7 said something widely unexpected (in itself not a rarity): He would support a ban on big institutional investors buying single-family houses, as an approach to apply downward pressure on housing prices. His proposal was not much more specific than that. It has not been followed up since, and the administration has been mostly silent about it.

Some members of Congress said they were interested. At least one Republican senator, Bernie Moreno of Ohio, said he would propose legislation in the area. But more Democrats, including Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, said they have been pushing for limitations on big-money buys of housing stock for some years, often meeting Republican resistance.

The senator most identified with the issue, though, is Merkley of Oregon, who for several years has focused especially on mass buys of real estate by hedge funds.

In October 2024, he offered a proposal that “bans hedge funds from owning single-family homes and forces hedge funds and other large private investors to sell their inventory of single-family homes to families who don’t currently own a home. If the hedge funds don’t, they are required to pay a substantial tax penalty that funds a down payment assistance program.”

How much impact corporate, institutional and wealthy buyers are having on the cost of housing has been hotly debated. Institutional investors (including hedge funds) may account for less than 5% of purchases according to some studies, but investors of other kinds may represent a quarter or more of all house buyers in expanding markets. Some studies in places like Atlanta have put the number as high as a third.

Of course, many people who live in the houses they buy also own them in part as a long-term investment, but that’s a different category and tends to have less effect on raising prices.

The effect of corporate and other big-money buying comes not just from adding to competition for houses, but more from driving up prices, since such investors could afford much higher prices — almost the sky’s the limit in some cases — than average home buyers could manage.

Only a small percentage of middle class home buyers can afford house prices a half-million dollars or more, but those sales points have held in place, and in some active markets continue to rise. Wealthy investors and institutional buyers are among the few market segments that can afford them; absent them, some of those higher prices might drop.

Members of Congress like Merkley and Warren have been interested in the subject for a while, but it is not the only place action could take place. It can happen, and might even be more locally effective, at the state level.

Housing prices last year became a hot campaign topic in one of Oregon’s border states, Nevada. It might yet find its way across the border.

In Nevada, a Democratic legislature has proposed a string of ideas aimed at limiting housing costs, several of which were vetoed by the Republican governor. The subject has become a centerpiece in the 2026 gubernatorial campaign there.

Late last year, Nevada legislators proposed Senate Bill 10 which was intended to set a ceiling on all corporate purchases of homes in the state to no more than 1,000 total. Advocates noted recent studies showing connections between high number of investor purchases of homes and rising home prices.

The bill failed by a single vote, but the idea is sure to return before long.

The same concept could be picked up in Oregon, as early as this year’s short session. Odds are that no such complex legislation would make its way through to passage so quickly, but it would be put on the table, for review over the year (and in campaign season) and teed up for more thorough action in 2027.

Such measures would not not be a complete fix for the problem, of course. The sheer amount of residential housing in Oregon needs to be increased (something the state has been working on), and that’s an essential element to providing more affordable housing for more people.

But houses are unlikely to become more affordable if big-money buyers with few limits on price keep putting higher floors under housing prices. It’ll be up to the legislature to do something about that.

Randy Stapilus has researched and written about Northwest politics and issues since 1976 for a long list of newspapers and other publications. This guest commentary is from news partner Oregon Capital Chronicle, and it may or may not reflect the views of The Corvallis Advocate, or its management, staff, supporters and advertisers.

Do you have a story for The Advocate? Email editor@corvallisadvocate.com