At a virtual press conference on Thursday, Oct. 9, Klamath River scientists announced that a year after the last of the dams were removed, river health has begun to bounce back. With salmon swimming upstream, bald eagles flying overhead, and increased bear, beaver, otter and osprey activity, the ecosystem is booming with ecological shifts thanks to the completion of the world’s largest dam removal effort.

“The rivers seem to come alive almost instantly after dam removal, and fish returned in greater numbers than I expected, and maybe anyone expected,” said Damon Goodman, Mount Shasta-Klamath regional director for California Trout, a conservation nonprofit that works to keep waterways and wild fish healthy.

According to Goodman, the fish monitoring effort done by California Trout is likely the most comprehensive science and monitoring project ever done to evaluate a dam removal effort. The monitoring efforts include sonar and video weirs that track the abundance of timing of returning fish, boat surveys documenting spawning habitat and distribution of fish, telemetry for migration behavior, netting and eDNA for tagging and species composition, and traps for downstream mitigation timing.

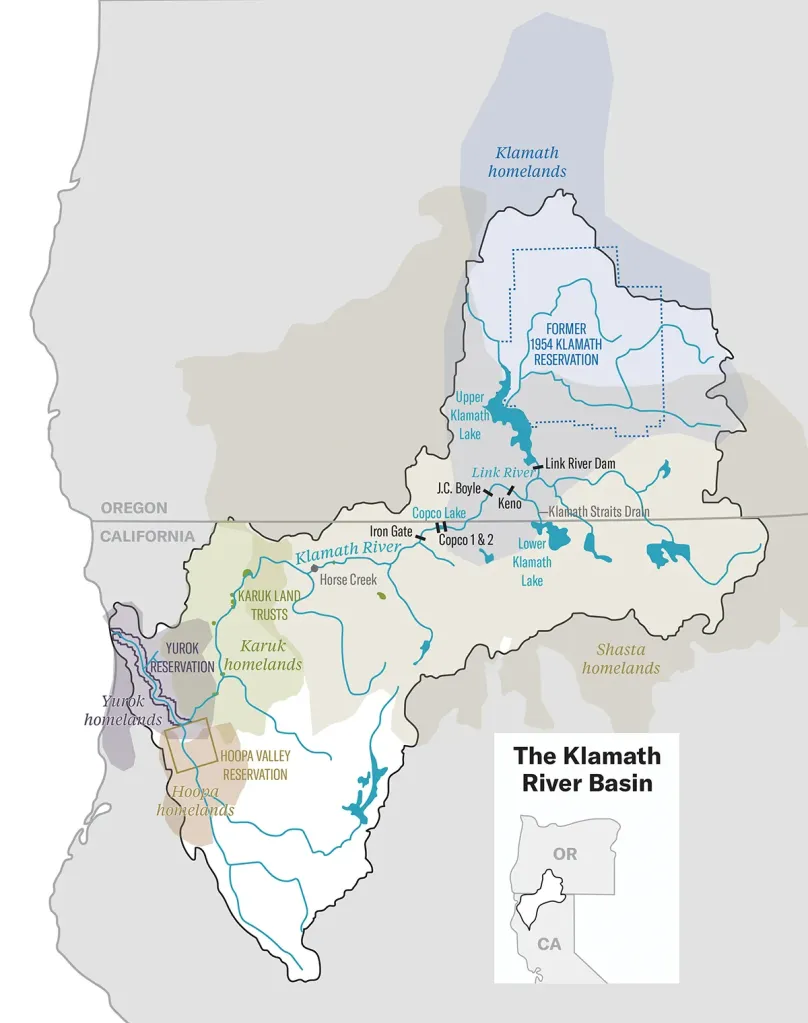

With data analysis, Goodman and his team have learned that 7,700 fish passed through the former Iron Gate Dam site between Oct. 2024 to Dec. 2024 with an average of 588 fish per day with Chinook salmon making up about 96% of the fish that made their way upstream. According to Goodman, fish returned to all of the streams scientists expected salmon to return to for spawning — a trait of their life cycle called anadromy.As of Sep. 24, researchers saw the first video of a Chinook salmon ascending Keno Dam fish ladder on the Klamath River and on Oct. 7 an image was gathered showing a Chinook salmon leaving the fishway at the top of Link River Dam and entering Klamath Lake.

“We detected fish in the sonar within the first week of dam removal,” Goodman said. “Within a couple weeks, they were all the way into Oregon spawning.”

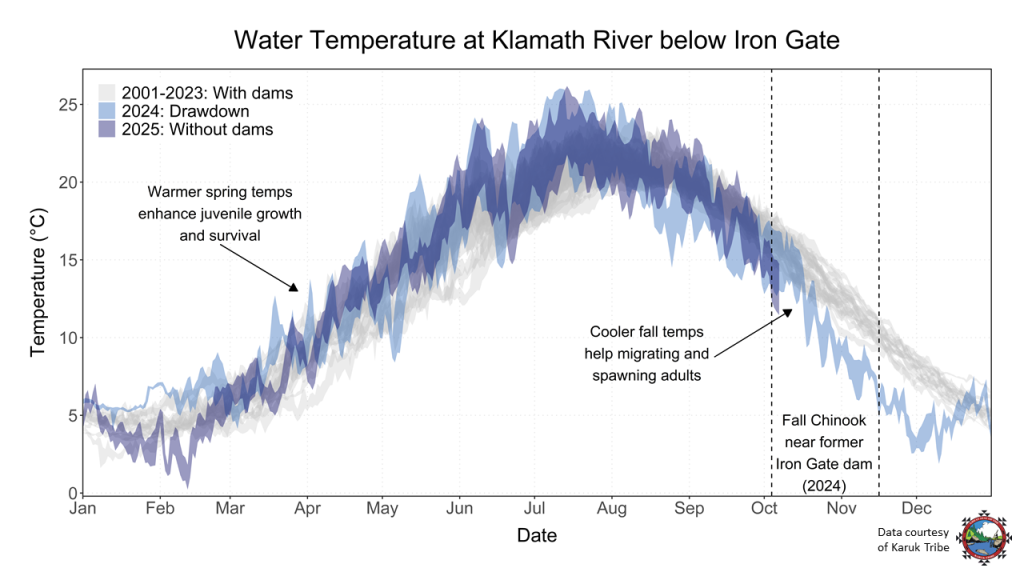

Cooling waters

Salmon rushing their way into the Klamath River is just one indicator of increasing ecosystem health in the area. The Karuk Tribe runs a network of real time water quality monitoring stations downstream of the former Iron Gate dam. Toz Soto, fisheries program manager for the Karuk Tribe, said the water quality has increased in the Klamath River due to the sediments settling from the dam removal and water temperatures naturally regulating.

When the dams were present, water collected heat over the summer resulting in hot water temperatures that lasted far longer than they typically would. Normally, a river would cool off but the reservoirs in place, which according to Soto were “heat batteries,” made perfect breeding grounds for harmful algae blooms.

Soto showed before and after photos during the press conference of a neon green toxic algae, known as microcystin, filling the former reservoir. Plants surrounding the area were brown and looked lifeless against the backdrop of the toxic water. But a year later, photos show clear non-toxic river water with wildflowers blooming in green grasses lining the riverbank.

Fishing for footballs

According to Soto, in previous years, 58% of water samples taken at the Klamath River below Iron Gate dam site were above the public health limit for microcystin which can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and potentially severe liver damage. Now, without the dams, 100% of the samples have been below the public health limits with 82% of the microcystin levels not even detectable.

Yurok Tribal Fisheries Department Director Barry McCovey Jr. said the Klamath’s improved water quality has made fishing easier for tribes in the area. Previously, suspended algae in the water would get stuck in the nets while tribal fisherman gillnet fished — a traditional way of fishing which the Yurok have done since time immemorial.

Fall-run Chinook salmon are entering the river earlier and traveling farther than they’ve gone in over a century, according to McCovey. Historically, the fish entered early to mid-August. The first year after the dams were removed, salmon journeyed the way historical accounts have depicted.

This year, the salmon were so robust and large, McCovey said they’ve been called “footballs” by tribal fishermen. According to Soto, the size of the fish can be tied back to cooler water temperatures. With the dams gone, cooler water temperatures are leading to fish migrating faster and doing so while burning less fat.

Although fall Chinook have had immediate success, the spring-run Chinook population is on the brink of extinction. Historically, spring Chinook salmon were the largest population of Chinook in the Klamath Basin prior to the dams being built, said Soto. Now, the Klamath’s population of wild spring-run Chinook is down to just a few hundred with the nearby Salmon River hosting one of the last viable populations of spring-run Chinook and a hatchery population on the Trinity River.

“The spring Chinook population today is basically on the verge of extinction,” Soto said. “So it’s a grave concern for us. But with dam removal, there’s a lot of optimism that we can recover spring Chinook.”

The future of the Klamath

Sami Jo Difuntorum, cultural preservation officer for the Shasta Indian Nation, said her tribe was largely impacted by the dams and with traditional villages practically being erased.

“We’ve been called the Tribe the dams were built on and it is literally true,” Difuntorum said. “The dams were built on our villages.”

After the reservoirs were drained the landscape was barren since vegetation hadn’t grown in the area for over 100 years, Difuntorum said. While people were immediately happy with the dam removal, Difuntorum didn’t immediately react the same way. It wasn’t until she heard the water coming through the canyon and the rocks popping as water hit them for the first time in 100 years, that she felt happy.

“What it said to me was the earth and the rocks were welcoming the water back,” she said. “And so that meant healing.”

Although the river’s ecosystem has been healing, Goodman said Klamath River monitoring work has been impacted by recent federal funding cuts, particularly the Department of the Interior’s decision to terminate CalTrout’s funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. He said the loss of funding was a setback for scientific data collection, but that the team is still seeking other funding.

“While we’re already seeing that the Klamath dam removal is a success, we need consistent and accurate data to understand how much of a success this project was,” Goodman said. “We’re currently fundraising to fill the gap for that lost funding.”

As McCovey talked with tribal members, tribal fishermen and sport fishermen in the community, he said, “there’s this feeling that the river just feels different. It feels stronger. It feels cleaner.”

Although the progress made in a single year has created hope, McCovey said, the Klamath is still in the beginning stages of healing from nearly a century of blockage, with “scars” that “are still fresh.”

“But the progress that we’ve made in just one year is pretty incredible,” McCovey said. “It provides us with a lot of hope for the future.”

By Lyric Aquino for Underscore Native News. Aquino is an award-winning journalist with a passion for writing about all things relating to science, the environment and Indian Country.

Do you have a story for The Advocate? Email editor@corvallisadvocate.com