During the 2020-2021 academic year, Dr. Luhui Whitebear (Coastal Band of the Chumash Nation), assistant professor at Oregon State University and Center Director of Kaku-Ixt Mana Ina Haws, committed to finding creative ways to decolonize the university classroom in a series of three courses: Introduction to Native American Studies, Indigenous Feminisms, and Indigenous Resistance and Pop Culture. The latter two, she hopes to make permanent at OSU.

Each class was designed to familiarize students with the historic and ongoing impacts of settler-colonialism on Indigenous peoples, and the longstanding methods of resistance Indigenous peoples have practiced and continue to practice in response to these impacts. Learning objectives were facilitated by having students contribute to virtual, community-based art projects.

“I really like using creative projects as final projects for coursework because of the hands-on learning that happens with it, and because of the application of what you learn,” said Whitebear. “It’s totally one of my favorite things to do, and I think it’s partially because I work at the center and I’m used to doing hands-on stuff with the staff through events, and so the way I teach is incorporating some of that as well.”

While having to teach classes online may have removed the tactile aspect, these projects still invited ways for students to recognize and uplift Indigenous struggles as living histories of intergenerational resilience. Both through these projects and in written reflections, students were able to learn how to identify and critique the effects of settler-colonialism to advocate for change, as well as engage with perspectives that have been subjugated, erased, gaslighted, and criminalized for centuries.

Introduction to Native American Studies

This Ethnic Studies course is intended to introduce students to Indigenous histories, as well as to raise awareness of Indigenous peoples’ current lived experiences and relationships with the U.S.

Under Whitebear’s direction, students had to create, for their final assignment, a page for a collective arts-based zine that reflected contemporary issues being faced by Indigenous communities. These included federally recognized, state recognized, and unrecognized Tribes in the U.S.; First Nations communities in Canada; Indigenous communities in Mexico; and Native Hawaiian communities.

“Part of what happens when teaching any type of Native Studies is that people will think of us as being in the past,” said Whitebear. “So I want people to find something that’s current, not something that’s from way back — even though all of it ties to colonization.”

The zine covers a range of issues relating to intergenerational traumas of land dispossession, poverty, cultural appropriation, the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls crisis, and natural resource extraction.

A few students contributed pages highlighting contemporary resistance movements led by Indigenous communities against extraction and construction projects on lands to which they have deeply rooted ancestral and cultural connections.

Across North America, Indigenous land defenders and water protectors have been leading the frontlines of direct action against fossil fuel expansion and resource extraction. But more than that, they have been actively confronting further desecration of ancestral homelands at risk of being cleared, depleted, polluted, privatized, bulldozed and built upon. From the Trans-Pecos pipeline to Fairy Creek to Mauna Kea and beyond, Indigenous organizers have been chaining themselves to earth-moving equipment, setting up camps and blockades, occupying the lobbies of corporate financial backers, etc. As a result, they have also been the most heavily targeted and criminalized within the climate justice movement.

Yet, while there is some growing recognition that supporting Indigenous struggles for sovereignty and decolonization is a key solution to the climate crisis, Whitebear noted that there’s not enough of a shift taking place within mainstream environmentalism.

“Outside of things like Standing Rock, Keystone, or maybe even the LNG project at Jordan Cove here in Oregon, those are very specific examples that people might know about, but if you think more broadly about environmental activism as a whole, it’s not always taking direction from Indigenous peoples,” said Whitebear. “I think art’s role in centering Indigenous leadership is to help raise awareness and also determine how the story [of environmental justice] is presented and told.”

At the height of the #NoDAPL movement at Standing Rock, Oceti Sakowin water protectors were able to achieve this in part by re-storying the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline within a longer history of colonial violence against ancient reciprocal relationships between land, people, and lifeways. Their messaging on the sanctity and kinship of water — precious, lifegiving, and deserving of protection — was informed by weaving in traditional storytelling and art with contemporary direct action tactics drawn from generations of Indigenous resistance.

“The Black Snake prophecy was really specific to Tribal communities over there,” said Whitebear. “It’s helping recenter their leadership by bringing in traditional stories as well as traditional art and representation.”

Indigenous Feminisms

Cross-listed as a course in Ethnic Studies; Queer Studies; and Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies, this 300-level special topics class introduced students to Indigenous feminist and queer responses to settler-colonialism. Topics included the longstanding organizing and care Indigenous women have provided to their communities, as well as their roles in reclaiming traditional knowledge and identities that settler-colonialism has sought to erase.

“Indigenous women have always had political autonomy and leadership roles, whether or not they were matriarchal or matrifocal, or if they shared leadership within their nations,” said Whitebear. “Historically and in contemporary times, Indigenous women have always had a strong presence within our communities… And they had a significant role in resistance to colonization, so part of talking about Indigenous feminisms is bringing those stories to the center.”

Being at the forefront of such resistance, consequently, has historically rendered Indigenous women targets for violence and exploitation.

“If you think about what happens around extraction, like temporary housing areas [for male construction workers], the sexual violence against Indigenous women and youth in general — not just girls, but Two-Spirit people and young boys, too — is really bad,” said Whitebear. “And I think that that’s often been used as a way to help frame those really deep connections to land and help us understand that land and body exploitation often go hand in hand. It’s helping us understand that not only is the land or the resources being extracted, and not only is the water or the land being polluted, but there’s also this violence happening towards Indigenous bodies at the same time.”

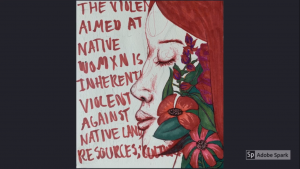

Whitebear expanded on this more in an essay featured in the anthology Persistence is Resistance: Celebrating 50 Years of Gender, Women & Sexuality Studies, writing, “The violences towards Indigenous bodies and lands are intertwined and part of the settler-colonial paradigm. At its root, Indigenous feminism is about these connections as well as the ways in which settler-colonialism has inflicted gendered violence on our bodies and spirits because of who we are as Indigenous people.”

Historically, one of the most prevalent manifestations of this gendered violence is the epidemic of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, and Two-Spirits, or #MMIWG2S.

“I planned on having the class do a Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s awareness event for campus, hold it during class, and invite the campus and community to that event, but the pandemic derailed that,” said Whitebear. “I ended up having [students] just do a creative project; it could be a painting, a drawing, a collage, a poem or a song.”

Using Adobe Spark, Dr. Whitebear assembled all of her students’ projects — a mix of poems and visual art — into a video. One student wrote and performed a song for their assignment, which can be heard playing in the background.

“Part of what I try to do in class was to highlight that this really messed up stuff is happening, but that there’s also Indigenous women who have done really powerful things despite it, like helping to restore Tribes, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, and Women of All Red Nations,” said Whitebear. “Indigenous women have really played a prominent role in acts of resistance and resilience, so I tried to be really careful because what happens sometimes is the story of violence becomes the story of Indigenous women.”

One Indigenous woman whose life and work students were able to learn about was Corvallis-born Kathryn Jones Harrison, former Chairwoman of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde who played an instrumental role in restoring the Tribes, and whom one of three Corvallis elementary schools was recently renamed after.

Indigenous Resistance and Pop Culture

The last iteration of the zine project for the academic year took place in spring term through another special topics class — Ethnic Studies 399: Indigenous Resistance and Pop Culture. Similar to Whitebear’s Intro to Native Studies class, for their final assignment each student had to create a zine page depicting various contemporary issues affecting Indigenous communities. Only this time, these issues had to be represented using elements of pop culture.

“I am a pop culture nerd,” said Whitebear. “I’m really into Star Wars, I like graphic novels and music, and it’s just another way to tell a story.”

Whitebear has expressed optimism in the ways Indigenous people have been able to preserve and reclaim their knowledge, cultures, histories and futures through their own use of pop culture. Students were able to see this for themselves by engaging with films, music, online games, graphic novels, street art, and other creative media by Indigenous artists.

Graphic novels that students read included The Outside Circle by Patti LeBoucane-Benson, 7 Generations: A Plains Cree Saga by David Robertson, and A Girl Called Echo, Vol. 1: Pemmican Wars by Katherena Vermette. Each tells empowering stories of Indigenous protagonists in their struggles to heal from centuries of trauma by learning their histories and reconnecting with their cultural heritages.

“Sometimes people will get really bummed out learning about Indigenous histories, understandably; I get bummed out about our own histories. It’s a really rough story because of the way that settler-colonialism operates, and I feel like pop culture is something that people can relate to, and it’s also something that shapes our experiences and how we see ourselves fitting into the world,” she said. “And so having all of this Indigenous music out — and graphic novels, fashion, and even film — has really allowed Indigenous people to tell our stories on our own terms instead of being misrepresented in those same elements.”

One student contributed a page containing a photoshopped image of the Indian Chief, a racist caricature from Disney’s 1953 animated film, Peter Pan. On the front of the character’s clothing is a collage of some of the myriad ways in which American pop culture — be it comics, cartoons or advertisements — has been weaponized to mock, appropriate, and dehumanize Indigenous peoples and cultures. In his shadow, however, lies a different — and often hidden — story.

At the foot of his shadow is a collage of black-and-white photographs depicting longer histories of Indigenous struggle, such as the coercive, violent assimilation of Native children into encroaching settler societies through the residential school system. These images then give way to color photographs — most of which were taken within the last few years, some even within the last several months — depicting ongoing, revitalized traditions of Indigenous resistance.

“If you think about the role of film and cartoons and all the ways that Indigenous people have been exploited and misrepresented, this [project] is like a complete turnaround on that,” said Whitebear.

Asa Wright, an enrolled member of the Klamath Tribes in Chiloquin, Oregon, touched on this succinctly in an artist’s statement for a poster he designed for the #DefundLine3 Arts Visibility Week of Action: “Through art we tell our story, keep our history and dream of the future. It connects us. It mobilizes us. It represents us. Art is the visual voice that shows others that we own our own narrative. That we are strong, resilient, and that we define our own future.”

Anishinaabe cultural critic Grace Dillon, an Indigenous Nations Studies professor at Portland State University, coined the term “Indigenous Futurisms” — an homage to Afrofuturism — in reference to a growing movement of Indigenous creatives reimagining decolonial histories and futures through popular visual storytelling mediums and speculative literary genres.

“[Art] helps visualize something that may not have been thought of before,” said Whitebear. “How can we imagine our futures that are based in Indigenous sovereignty and Indigenous teachings? Art provides an entry point to think about that and to actually see it happen, whether it’s through video games or through music videos or film. The whole purpose of it is to help us think ahead in ways beyond what we’re existing in.”

Continuing the Work

Whitebear is currently teaching Intro to Native Studies again this fall, which will have another zine project that students will be contributing to. While the Pop Culture and Indigenous Feminisms courses were special topics classes, she hopes to teach them again in the future, and plans on applying for them to be permanently on the books at OSU.

As of this year, Whitebear’s role on campus has expanded to Assistant Professor for the School of Language, Culture, and Society — a position which will allow her to advance Indigenous Studies at OSU with distinctive expertise in Indigenous methodologies, feminisms, and California Indian Studies. She is also continuing to provide academic leadership to the munk-skukum Indigenous Living-Learning Community — now starting its second year — members of which have the opportunity to enroll in the Intro to Native Studies course each fall.

“We are all existing in a time where we are often asked to separate ourselves from feeling and from connecting to learning,” said Whitebear. “Creative projects ask us to feel, both internally and tangibly, which is another way to think more deeply with topics as well as think of how to keep those connections going in the future. My hope is that students are able to take the underlying lessons into other parts of their lives beyond the classroom as well.”

By Emilie Ratcliff

Do you have a story for The Advocate? Email editor@corvallisadvocate.com